Sort Analysis Spreadsheet Link

Bubble Sort GitHub

Insertion Sort GitHub

Selection Sort GitHub

Many people judge the performance of sorting algorithms just by their worst case time complexity. However, there are many more factors to consider.

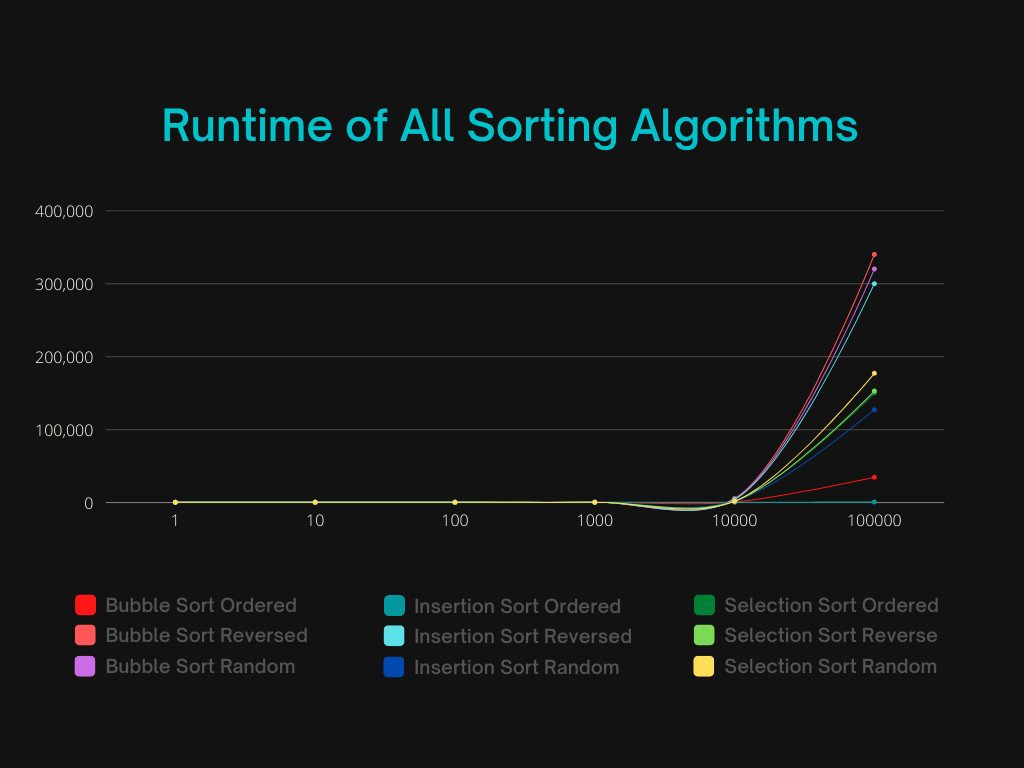

Bubble Sort, Insertion sort, and Selection Sort all have a worst-case time complexity of O(n^2). This means that in the worst case, the runtime of the algorithms should vary proportionately with the input size squared, as you reach bigger input sizes.

As we can see in the random part of the graph, insertion sort is usually faster than selection sort, which is usually faster than bubble sort. Bubble sort usually has ~n passes, where each pass has ~n comparisons and up to n swaps. This will usually result in n^2 comparisons and up to n^2 swaps. This is slower than selection sort because although it usually has the same number of comparisons (n^2), selection sort will only have a total of n swaps, which is better than bubble sort most of the time. Insertion sort, on the other hand, will have n passes, but in each pass, it will only perform the number of swaps and comparisons needed to get the element to the right place, which takes half as much on average. Also, the length of the sorted part of the array grows from 0 to n throughout the sort, so the length is 1/2n on average. This makes it have an overall of ~(n^2)/4 swaps and ~(n^2)/4 comparisons on average, which makes it faster than both bubble sort and quick sort.

However, in the ordered part of the graph, we see different results. Insertion sort and Bubble Sort are both faster than Selection Sort. This is because Insertion Sort and Bubble Sort are adaptive algorithms. When the data is already sorted, each pass of insertion sort makes no swaps and only one comparison, making its best-case time complexity O(n). With bubble sort, if no swaps are made in the first pass, the algorithm stops, making it's best-case time complexity O(n) for already sorted data. Selection sort always has to make n comparisons when looking for the minimum in each of its n passes so it always stays O(n^2), even if the data is already ordered.

In the reversed part of the graph, insertion and bubble sort have much worse runtimes than selection sort, because they have to perform the maximum/worst-case number of comparisons and swaps (n^2 for both). Selection still has n^2 comparisons but only n swaps, so it's faster in the worst-case.

In real life data, random (average-case runtime) data is most common, and somewhat ordered data is also common (which has a runtime between best and average-case). Out of these algorithms, Insertion sort seems to be the best sorting algorithm overall, because of its adaptability and good average runtime. Even though insertion sort is worse on reversed data, reversed data is not common in real life.

My teammates were Joshua Lee, Connor Church, and William Clymire.